Juan Davila

Juan Davila

born Chile 1946; arrived Australia 1974

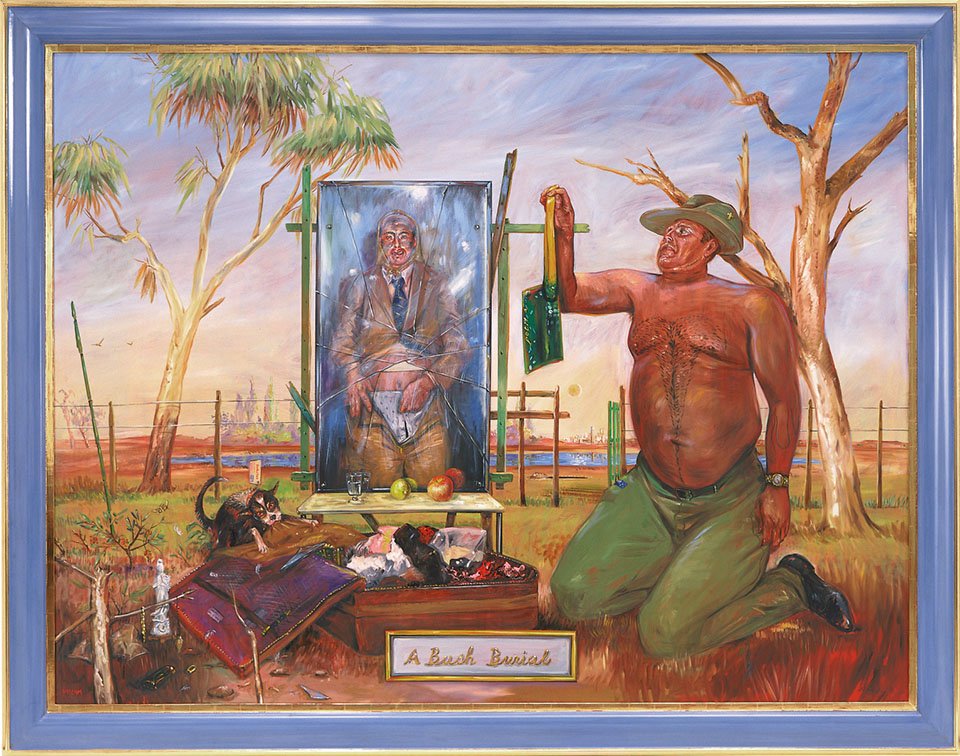

A bush burial 2000

oil on canvas

Geelong Gallery

Gift of the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and the Geelong Gallery Foundation, 2001

© Juan Davila, Courtesy Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art

Since his arrival in Australia in 1974 from the political upheaval engulfing his native Chile, Juan Davila has become one of Australia’s most critically acclaimed and uncompromising artists. Davila believes in the possibility of effecting social change through art. His work draws on a vast array of historical and contemporary references and situations, and it is deliberately and often provocatively political. Davila’s imagery consistently tests and questions cultural, sexual and social identities and he is especially engaged with Australia’s Indigenous history and present, in the context of our country’s complex social diversity.

Davila’s A bush burial derives its title from Frederick McCubbin’s iconic 1890 painting, acquired by the Geelong Gallery in 1900 and displayed in the next room. McCubbin’s melancholy image under-scores endurance and hardship, but also signposts the sacrifices and achievements of pioneers as they colonised and settled Australian land.

Davila’s version is from a series of large-scale paintings that chronicle episodes in the imagined life of the artist’s alter ego Juanita Laguna—the dishevelled, dispossessed figure of the ‘other’ whose reflection we see in the broken mirror.

In this work Davila asks us to consider the humanitarian and social crisis of the asylum seeker and the refugee. Since 2000, the issues and images of migration and detention have recurred in Davila’s art, re-presenting some of the disturbing narratives of contemporary politics. In this work, the sunlit city reflected in a seemingly idyllic landscape is counterpointed by the menacing, freshly-dug grave in the middle distance, and the scene of degradation or dystopia in the foreground.

The figure of Juanita has arrived at the gateway to a new and promised-land only to have his/her luggage torn open, brutally examined and, it appears, held to scorn, by a burly, bare-chested customs official—degraded himself by blind nationalism. The rabid dog is a century away from McCubbin’s loyal and sorrowful pet at the graveside.